This article will perhaps be the most updated and modified of the blog, because being based on my experience and others, it will necessarily evolve with it: I hope, for the better. Enjoy the reading!

Before writing your awesome – or shitty (͡ ° ͜ʖ ͡ °) – fantasy saga, it is essential to name everything on the map, because the plot design will start from there. How many look for a long time at the map printed on the very first pages of the books? I think hardly anyone, except for a quick glance. But if the reader gets confused during the narration about a place or a shift of the characters position, that’s where they will go. This is why books of this genre without a map at the beginning, as the ones belonging to The Witcher saga, can be confusing; especially if there are often scenes of politics, strategy, or even just discussions about different realms. If you really decide to take this risk, so no map at the beginning of the book, well, you have to do one anyway: because if you write a saga without knowing where things are (or you know it by approximation), an ostrich shit will come out. To name stuff on the map, you need…

… a map.

And it is not easy to think about it, nor to do it in a realistic way: many small things that seem futile at first, often simple notions of geography that you would have taken 3 seconds to internalize, can lead you to a sewer map. We will then analyze everything, from start to finish: we will begin with the instant you place the pencil on an A4 sheet, passing through the actual map and ending with the commission of the same to an artist.

This stuff I learned on the the internet and by trial and error, so although notions are quite widespread online and often also intuitive, consider that they are not taken from a high-level manual, but from my experience. People much better than me have addressed the topics proposed here, especially on Reddit and personal sites, I will report all the sources at the end of the page.

Final ass-covering period: If you show the article to a climatologist or even just a graduating student in Geography, they will probably laugh in your face, and with good reason. All of this has no intention of being schoolish, and in nature there are so many exceptions to the rule that you could probably disprove every single point analyzed here. This stuff only serves to draw a base map that is generally realistic and plausible.

Contents

The draft on paper

The temptation to jump into the first free software suggested by Google is strong, and I did too. Once this happened, however, I think it would have been much more useful to start small from the classic, old draft on paper. This is because you will change your mind three thousand times from the first sketch to the last change, especially while you are still in the creative phase.

Preamble: Avoid creating entire mapped worlds. You should take into account an astonishing number of additional factors, from curvature to geographic consistency, and doing so requires skills that go far beyond those of one or more bloggers. A continent, often a region are more than enough to host fantastic stories, be they fantasy or an RPG like D&D.

You will have to do a few steps:

World division

- Decide in how many nations / kingdoms / parts and so on you want to divide the world;

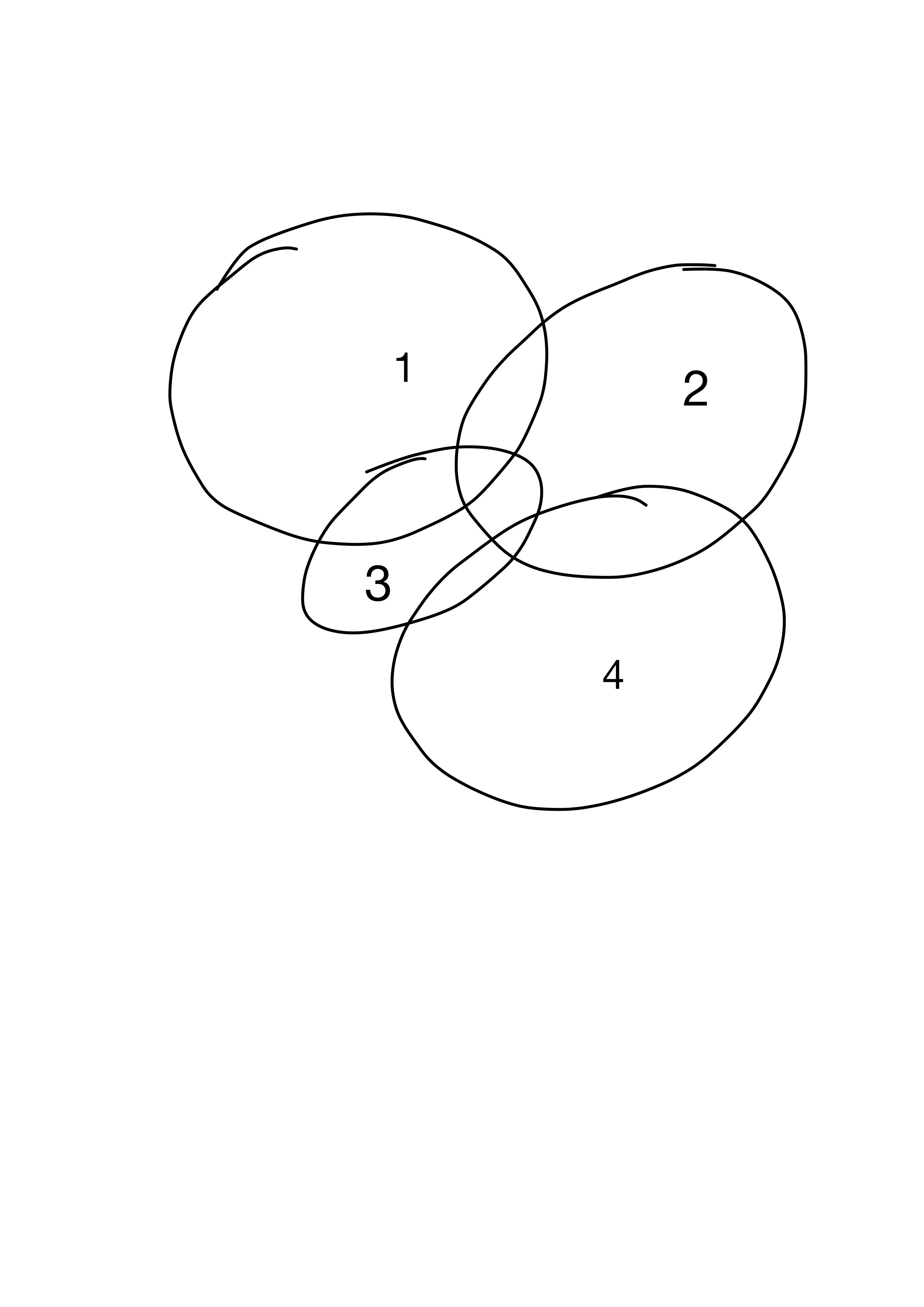

- Sketch them on paper and number them

It will be much easier for you to create a map if you already have in mind the powers involved, meaning which nations, empires, kingdoms and so on are contained in it. If not, no problem: choose an arbitrary number of parts ranging from 3 to 6-7, the more it starts to get complex.

Simply draw intersecting circles on the paper, and number them. Consider that your continent or region will be well or badly contained in these circles, so they will roughly have a shape defined by the “outer” limits of the various circles. Now, number them. You can already have names for each kingdom, part or whatever it is, or not: little changes, consider that we are still in the very early stages, the important thing is to understand how many there are.

Drafting the parts

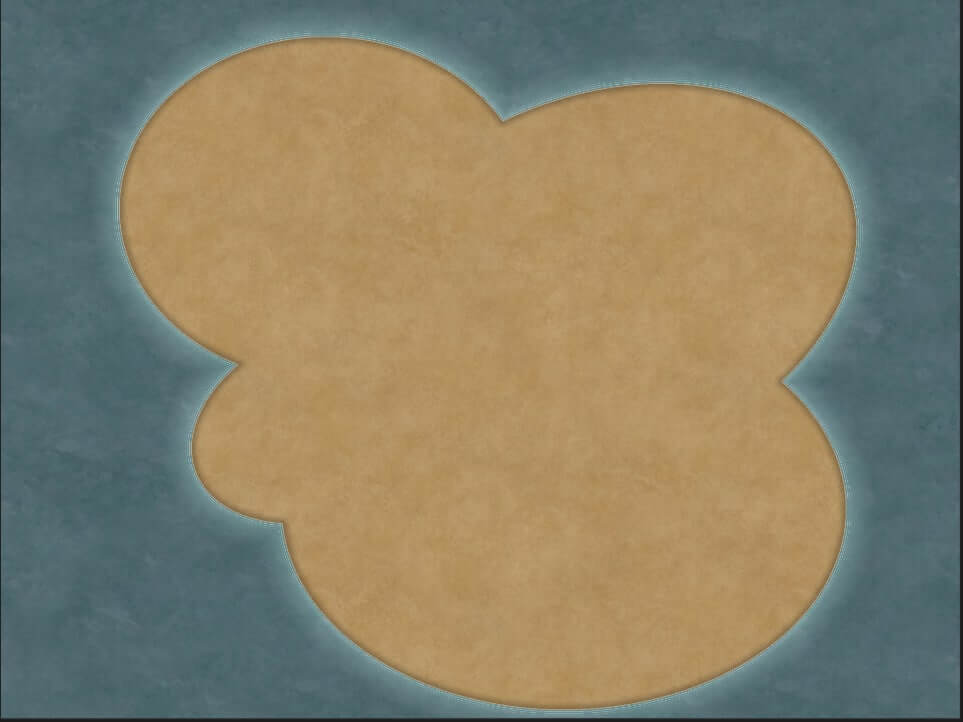

Here the donkey stumbles, and begins to fall. Drawing even a sketch of the map is a nightmare, literally, if you don’t use proper software or if you are not an artist who fiddles with Photoshop and / or graphics tables of any kind. You can always use the brush function of many very simple programs (from Paint, to Goodnotes, to a thousand others) but the truth is that, if you are not an expert, throwing yourself into a manual map design is asshole, and it will only take you two. things: learning a lot, and frustration. You are a writer (or a Dungeon Master), not an artist!

So, software or paper?

Software for life. There are several free, and more or less automated. Some examples:

- Inkarnate → the one we will use later, because it has a free version, totally online and foolproof;

- Wonderdraft → Younger brother of the fantastic Dungeondraft, requires one-time purchase and installs directly on your computer. It is not free, but it allows much more customization than the free version of Inkarnate;

- Azgaar’s Fantasy Map Generator → Generates a preset that will then be quite editable, on the other hand it allows the display of the political, geographic, etc. version of the map;

- Autorealm, Planet Creator, Roll for fantasy, Donjon → Stuff for RPG nerds, leave it be :D.

From here on out, it is assumed that you know how to use at least one of these software, simply because doing a tutorial on Inkarnate in the same article that talks about worldbuilding would get it to the level of Proust in terms of brickwork. Don’t worry, the tutorial is on its way, and it’s so simple you can learn it easily.

First version of the map

Much of the geographical notions in this section are taken from the exceptional Mythcreants. We will proceed in this order:

- The coasts

- Mountains

- Rivers

- Lakes

- Vegetation

- Civilized places

- Roads and political borders

The coasts and oceans

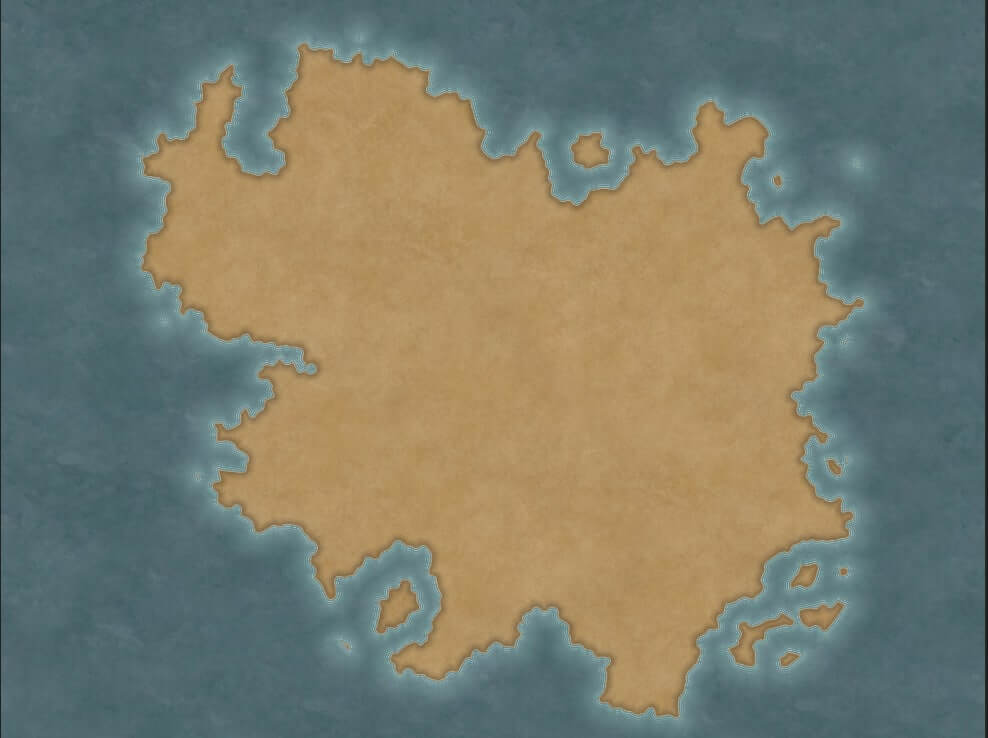

This is easy. Anything that is not earth will be water. The coasts are nothing but rock “raised” by collisions between tectonic plates and, pouring water all around them, you will highlight a recurring fractal type structure. Not the mathematical concept, simply every coastline will be visible, at sufficient magnification, as abrupt, straight segments joined together in a variously convoluted way. This almost always, with many exceptions, of which I report the main ones here:

- Mountains, glaciers and any combination of them will alter the coastline and do not follow precise rules, the examples on Earth (Norway, Chile …) are convoluted and complex, so you can indulge yourself in a fantasy world.

- Rivers deltas

- Coastal areas full of barrier islands nearby

Placing coasts

If you want a realistic map, remember that the earth tends to create continents and you will hardly find a series of islands or archipelagos as the only areas of land in the world, an example of unrealistic terraforming from this point of view can be found in the Earthsea world map . If you put mountainous coasts, with fjords similar to Norwegian ones, glaciers and so on, put them in the polar areas as a climatic zone. Insert a couple of barrier islands parallel to the coast, less square and linear than the coast.

For everything else, easy: make rough and fractal coasts, you always get it.

Mountain areas

How mountains born

In large part they are the result of continental tectonic plates that collide, regardless of the possible sliding of one plate under the other or their colliding with each other, the surface of the plate is raised from the ground level and forms the mountain. They are also formed by accumulation of debris and volcanic eruptions.

If you want to insert a volcano, they are the result of collisions more at the edge of the tectonic plate, particularly along the abyssal trenches, and along the oceanic ridges. You don’t have to justify in any way the presence of lava in your fantasy world, as it is stuff that comes from underground (technical term).

If an asteroid or a giant magical explosion creates a crater, rings of mountains will form all around it, and if the crater is large enough, an inland sea or lake will likely form there.

How is the climate affected by the mountains?

Mountains tend to be colder and wetter than their surroundings, and often act as separators between two neighboring climatic gradients. Not between desert and dense forest, so to speak, but between gradual transitions. There are exceptions, however, with mountains that have altered the surrounding territories so much that they profoundly changed their biome (see Death Valley).

Placing mountains

It is very difficult to find the single very high mountain on whose peak the classic wizard lives. In a topographically realistic map, the mountains will be in more or less linear columns or clusters. Consider that the islands are the result of the same process that forms the mountains: the ground rises from the previous level and, if this happens in the water, this generates islands or peninsulas. It therefore makes sense to arrange islands and peninsulas “along” the lines of mountains imagining them as extended into the oceans / lakes beyond the earth, for practical purposes imagine a line that continues along the mountain range beyond the coast manifesting itself, in the water, with emerged islands.

Around the large mountain ranges, there will be smaller mountains, then high hills, and finally a gradual loss of altitude until you return to base level. Indicate them, if you can, on your map. If it’s a continental map, you should only see mountain clusters, but if you have the scale of a small European country then it makes sense to be able to tell them apart one by one. This is because, if you have a map the size of Europe, you cannot place a mountain named Pedro visible at that scale – it would be impossibly large in size and would be inconsistent with its surroundings (this is a subtlety actually, you can ignore it).

The rivers

These follow a very simple logic: they start from an area higher than sea level, whether it is a mountain or not, and go to the sea. In doing so, they tend to follow the simplest and most direct path: they do not split into further branches of water, at most they unite as they flow towards the coast. Often the rivers are inside canyons and structures they have dug, and it is not strange that rocks, glaciers and more (in a mountainous region, for example) block their course, forcing them to follow another, but with the same rules as before. Forget about loops, rivers that flow towards the mountain and not from it, rivers that connect the oceans … they are not realistic. Here too, there are exceptions: the Po river in Italy, for example, certainly does not follow the simplest and most logical route to the sea, but curves and does its shit for unknown reasons.

What could be easily manipulated for our purposes, however, is the artificial deviation of a river through the intervention of sentient races, often for the purpose of construction or agriculture. Rivers are also likely to change seasonally, for example with periodic rains or during spring de-icing. You can put river beds that have now disappeared, rivers that are always frozen, and so on, as long as their localization is consistent.

Placing rivers

Do not put rivers that cross an entire continent, it would imply that for a while they flow uphill from sea level. Each river must start from a mountainous area (usually) but also from lakes, particularly humid wooded areas, or hills, and must necessarily end in the ocean, another river, or a lake. The important thing is that it never ends at an altitude equal to or higher than the one at which it started (so no rivers that end in the same point from which they start).

The lakes

These are usually linked to two factors: the ability to empty into the sea, and the presence of a tributary river. Any concave area or anyway depressed compared to the sea level is eligible to create a lake.

If it is an area entirely within a continent, landlocked and no river empties into it, it is possible that a small salt lake has formed at its most excavated point, and that the water there is salty, because of the accumulation of salt crystals over millions of years without it could end in the ocean.

If, on the other hand, a river flows into that area and / or it rains often, the depression fills up to the limit, then the water will begin to come out from the lowest possible point, flowing towards the sea. In this way it is possible to form areas full of small lakes connected by a network of rivers, especially if the ground is rocky and the waterways cannot easily dig it.

Placing lakes

You don’t have to justify small to medium depressions in terms of size on your map. Huge lakes, on the other hand, must be justified: on Earth they are due to melting glaciers, detachment of continents due to tectonic movements, and asteroids.

Consider the urban implications of having a lake nearby: if there is water, there will likely be people.

It always justifies the presence of a lake: rain, rivers, and so on. If you put them in a cold and fairly flat region, zero problems, but don’t put too many in desert areas, or at least justify their presence: it makes no sense that a mega-lake created by a river is in a desert, because around the water it is likely there will always be flora and fauna, as long as it is not too acidic or has unusual characteristics.

Very realistic and nice to see is the river that, in flowing towards the sea, “stops” in several lakes along its path (especially in cold areas).

If you place a lake near mountain ranges – and it makes sense to do so topographically speaking – it is plausible that they continue into the lake, manifesting themselves as small islets within it, just as happens with the islands beyond the coasts.

The vegetation

The maps usually shown in fantasy books and those used to play RPGs are almost never geographic, so they do not show land unevenness, wooded areas, and so on. However, it is useful to have the great forests on the map, because they influence travel, commercial crossroads, relations between peoples. Vegetation largely depends on the climate, which in turn is related to latitude. In reality, the climate is influenced by vegetation, more than the other way around, but here we are only interested in not making blatantly wrong crap in placing our saplings on the map.

A few general rules:

- The climate will be distributed in 5 total climatic bands, from the equator to each pole: equatorial, tropical, subtropical, temperate and polar.

- Along the equator, the climate is dry and hot.

- Near the temperate regions, located about 2/3 of the distance between two poles (therefore one above and one below the equator), the climate is humid.

- The rest of the areas are largely dry, about 1/3 the distance between the two poles, and cold and dry at the poles.

Placing vegetation

Decide what kind of area (s) your story will take place in. Do not fall into the classic shit of “here is desert, here is tropical forest, here is Jesus, and all in 30 square km”. Just think of Europe, and how gigantic it is as to be almost unusable as a reference model: there are no great changes in vegetation in so many millions of square kilometers. If you want to include areas that are diverse in terms of vegetation and environment, the climate must play a role. Generally speaking, you can put:

- Polar area, or in any case very cold

- Part in dry and cold weather [1/3]

- Equatorial part in tropical climate [2/3]

- Hot and very dry equator

- Equatorial part in tropical climate [2/3]

- Part in dry and cold weather [1/3]

- Polar area, or in any case very cold

This is if you consider an entire globe. Your story can take place in a continent that falls in part in the dry and cold belt, in part in the tropical one and finally in a dry equatorial area, almost desert. The important thing is that there is consistency in the order of the climatic bands chosen.

The type of vegetation depends on what you want to put into your world, and you have to do it yourself: if you have a very cold area, document what shrubs, trees and the like are in similar areas on Earth. Use those, or come up with coherent ones in terms of climate plausibility.

Depending on the software you have chosen, you will have various options to indicate large clusters of trees: arrange them according to the climatic bands and note what type of flora it is.

Civilized places

They must necessarily be inserted after having created the geography of the continent. This is because all civilized places are in strategic points, no one excluded: inserting cities in places clearly unsuitable to host them (no rivers or oceans, no commercial crossroads, river delta, icy mountains …) steals a lot of realism from the map. In the history of the world (ours), people have always built where it was worth doing.

Placing cities and other civilized places

- Gigantic cities: only in places of maximum strategic importance, are they commercial crossroads, with nearby water, flat and not impervious terrain, usually temperate climate. This is because trade is made much easier by water, especially by sea, but on the other hand, rivers also offer water that can be used for agricultural purposes.

- Small and medium-sized cities also along the coasts and rivers. Nothing prevents you from making the small city of dwarves planted on the top of the mountain, but you have to find a justification: even a simple “Here are mines of x, therefore it has very high commercial importance” is perfect. There must be a plausible reason why an entire city remains there, in short.

- Fortifications or small towns away from rivers and so on are possible, but usually have strategic importance: mountain passes, islands, on top of hilly areas, and so on. They can only develop in worlds where there is a minimum of stability: if there are large and medium-sized cities on average advanced, it is plausible that they supply these remote places with provisions and people to maintain strategic control of the area.

In conclusion, put most cities along rivers and coasts unless you have a good reason – given the story you’re writing – not to.

The roads

The roads must be marked on the map with a different color or brush than the rivers, otherwise you risk getting confused. They will have to connect all the most important urban centers, therefore given that the latter are almost always located near streams, lakes, or along the coasts; it is plausible that the roads often find themselves lining rivers, or in any case they will pass in their vicinity. Before placing a road, always put yourself in the shoes of the people you are populating your continent with: if two cities that have a reason to be where they are find themselves separated by a mountain range, does it make sense that a road is built and maintained to connect the two sides of a mountain just to connect them? The justification of trade is not always enough, consider that we are roughly in the Middle Ages, a road through the mountain is certainly not a modern tunnel in which you pass by car: people still have to do a lot of trekking to get to one side on the other hand, then forget about large movements of goods through wagons, the use of mules and other climbing beasts is much more realistic, limiting the number and quantity of marketable goods. Perhaps, however, through the road along the mountains precious stones are traded, also lending the side to secondary and interesting stories, I don’t know, bandits who settle permanently near the mountain because they know that merchants in difficulty pass through there: that’s why precisely the heroes of your story (or the D&D campaign) are called in!

Placing roads

Just use a different system to indicate them, so as to distinguish them from rivers. Run them often near rivers, create a network of them that interconnects the various cities, and ask yourself whether or not it makes sense for one or more roads to pass through mountains or other natural limits to connect points of interest.

Political borders

They are extremely important to most stories, and as much as you find them in maps, you will rarely find them even as actual physical marks on the ground. When we still didn’t have Google Earth and people used to shit in buckets, borders were often defined just by obvious geographical limitations, such as mountain ranges and rivers. The only thing you must not do is create political boundaries that do not take into account the obvious behaviors of the population: dividing a valley into two different kingdoms is possible, undoubtedly, but do not expect the rural population of the place to respect an imaginary line of which it barely knows its existence, but will tend to expand as long as it can within the fertile territory that lies ahead. A river that divides the valley, on the other hand, is a much more effective divider and it makes sense that it marks the (respected) border between two different peoples.

How the boundaries are drawn depends on what led to their birth: if they were born naturally and follow geographic boundaries, they are likely to be blunt and convoluted. If, on the other hand, the territory has been the subject of a conquest or there has been a clear division of the various geographical areas (for example between the heirs of a deceased) it is much more likely that the borders resemble those of the African states here, they seem to practice layouts with ruler and square.

Placing borders

Determine what is the reason that led to the creation of the borders. Make them linear and square if they are the result of bureaucracy or conquest, or let them follow geographical limits if they arose naturally over time. The division between the various kingdoms of uninhabited and inhospitable areas, for example, will be done with a row and a team.

Map’s scale

This is a common problem for those who approach mapmaking: we tend to make gigantic maps, because we often fall into the big history big map, regardless of the purpose for which the map itself is intended.

There is a notable dilemma, however: the vast majority of fantasy worlds are in a medieval stasis, or at least around year 1500 technologically speaking. No cars, planes and so on. Is there the magic to get around? Well, but either your story is particular at least (everyone has magic at their disposal), or there will be assholes teleporting from one side of the map to the other, and the rest of the world has to literally be with their feet on the ground.

Plausible traveling in medieval times

As an approximation, you can consider that:

- Giangiovanni, a fantasy drug dealer, traveling on horseback can travel around 64-96 km per day.

- Franco, a poor loser who breaks his back in the mine, can travel about 16-32 km a day on foot, more if the road is well maintained.

- The Culini family, using a towed wagon, will travel 32 km a day on average, and will only be able to travel on well-maintained roads.

Do you see what the problem is? If you make a giant map, it could take your heroes literally years to move from one place to the other, not least because these numbers refer to trips to clean areas, without toxic bandits in ditches or swamps full of alligators. So either you do some remarkable time-skips, or you provide the party with means of rapid movement (read: magic), and at that point everything becomes surreal, or rather, difficult to manage in terms of narrative plausibility and coherence.

Boring excursus on population density in the Middle Ages

So let’s ask ourselves how big a continent has to be to justify crisp stories, involving thousands and thousands of soldiers, wizards and whatever you want. Now, it must be said that medieval population density was very volatile, for simple reasons: people died easily. Because of that, we have only estimates, which in turn are often expressed in intervals and not numbers. The population in 800 AD it was different from that of 1000 AD, and so on. Europe, excluding Russia, had about 10.178 million square km with a total of 79 million people, and about 95% of the fourteenth-century European population lived in rural areas, in villages and castle-towns. About 92 cities had 2.6 million total people, and only 5 of these were home to 650,000 of them. Another 87 major cities with 22,000 people each, and 118 cities with 12,000 people each.

Large, empty areas had few or no cities and semi-tribal political organization, and for more urbanized areas there was a minimum density of 8 people per square km. The less populous areas of England were placed like this in 1300, probably a little more, while Spain and Portugal stood around 18 in 1000 AD; but this does not require you to have only large cities in highly populated areas, indeed, between 1000 and 1500 Denmark maintained the same numbers through rural communities and farms.

For extremely urbanized areas, understood as cities with 100,000+ inhabitants, there were about 24 inhabitants per square km: similar cities could be counted on the fingers of one hand in 1300 (Paris, Milan, Grenada to 150,000, Florence and Venice around 100,000) .

You understand yourself that it is impossible to create a completely realistic map, who the hell is inventing 200+ names for cities and another thousand for various villages?

GIVE ME PRECISE RULES DAMN

Few, simple rules to not mess up your life and create a scale map that if it is not really realistic, at least it’s not shitty:

- Any self-respecting fantasy world will have at least one BIG city, super crunchy, heart of the empire (or something similar). It will be our fourteenth-century Milan, in short. For each city like this you put in, calculate 100,000 to 150,000 people. Consider that such an aggregate of people involves problems: somewhere you will also have to empty the intestines, work, and so on. Similar cities arose only at very important commercial crossroads, in areas not geographically disgusting (so forget the peak of the mountain, the delta of a river …);

- Each big city you enter will have between 18,000 and 22,000 people – they are still huge centers, which must have a sense of being there. They arose in coastal areas, along rivers, and so on;

- Each average city will have between 10,000 and 12,000 people.

- The rest of the map will vary between 8 and 18 inhabitants per square km.

So, what scale do I choose for my medieval world?

It depends on the breath of your story. A map as big as Europe is endless, huge and useless for 99% of fantasy worlds, as you can see from the image already scaled. As an approximation, do this: after having drawn the whole map using the instructions, including all the various towns, large cities, villages and castles that you like, calculate with the data above how many people there are in total in the cities. You have therefore only obtained the numbers derived from the urbanization. Back in medieval times where in one way or another we try to get inspiration for our fantasy books or D&D campaigns, however, 5% were making big money in the cities, while 95% of the people lived in the holiday home in the countryside, so do the proportion: [Total number of people in the city]: [0.05] = [x]: [1]. Basically divide the city people by 0.05; and get people in the countryside. You add them up, and you have the total people.

Example: You place the large and small cities you want on your map without scale. You have 300,000 people in the city. 300,000 / 0.05 = 6,000,000 people in the countryside. So 6,300,000 total population.

Knowing then that the average population density was between 8 and 18 people per square km, move the number towards the two extremes based on how populated the continent you want. When you have chosen which number to use, divide your total population by that number, giving you the total square km of your map. At this point, search for a nation or continent on the internet that has that size (approximately): you will use it to help you on the scale.

Using the map

Now you have completely created your map, you have made a dozen revisions and, even if you are not yet completely satisfied, you feel that the map is more or less ready. What are we doing now?

Do you need to give a name to everything?

We come to the names now. Avoid, if you can, names that are too similar to each other and / or meaningless: it is okay that the elves of your world speak their language and through it they have given names to their cities, but a reader who finds himself names like “Algreissxa” and similar amenities for every damn point of interest on the map, it will be confusing. My dispassionate advice is to give names as you like, but then to at least associate them with a quirk, a sentence or whatever, in English.

Example (stupid): Algreissxa, from the ancient elvish, but on the map and in the common culture everyone calls it “Shittyleaves”, because it is almost impossible to keep the streets clean, given the continuous change of foliage made by the magical trees of the ancient people.

Returning to us, yes, it is absolutely necessary to give names to everything, the when and how will depend on the use you will make of the map:

- For a D&D campaign → the first thing your players will try to do, immediately after the start of a new campaign, will be to try to get their hands on a map of the territory, unless they have already succeeded (and it is plausible that they can) through their backstories. You can’t afford to leave unnamed points on the map, it wouldn’t make sense, unless you are talking about uncharted territory, where at that point you will limit yourself to a “Wilderness” or something similar. For everything else, you will have to give everything a name, because the maps from which world is world are meant to allow orientation, it would be stupid to sell them without names.

- For a fantasy story → this is much simpler, because the reading public will not see the map until the book comes out. This allows you to be able to edit it until the last moment, and it is a huge advantage, however you have to follow some precautions to avoid finding yourself with geographical and narrative inconsistencies that would force you to revise the entire story.

- Name things you already know how to name or will use shortly.

- Anything that you still don’t know how to name or whether you will use it or not, but it is still there, will receive very sad and generic numbers. City 1, Forest 3, Mountain 47, and so on.

- Whenever a character refers to the location in the story, he or she will easily indicate city 1 or forest 3.

When you have a name to give them, do it. If you have used them in the story, use the word replacement feature of the writing software you are leveraging and the problem is solved. The important thing is to have kept the narrative coherence, because if a character refers all the time to a city that does not have a name or a number, you risk getting confused both in the revision and drafting phase.

Here free softwares die

Alas, pretty much all free software stops there. They will allow you to make an absolutely decent map with dignity, but customization is almost never possible. And, in fact, that’s okay with us: we’re not artists! The map is needed to write your book or create your RPG campaign, you certainly don’t have to sell it or have any artistic pretensions whatsoever. Export your map, as basic as it is, it will do the job perfectly. Mind you, unless you are a hoax, this is not the map that will end up on the first pages of your fantasy book. Whether you want to self-publish or a publishing house takes care of it.

The possibilities from here on

At this point you have two options: proceed to acquire artistic skills and carry out your map on your own, or contact someone who can already do it. If you want to use it for an RPG campaign, I advise against doing both, keep the map as it is and you will see that it will be more than enough for your purposes. If, on the other hand, you publish a book with a publisher and not through self-publishing, zero problems, give them this version of the map and they will commission someone to make the final one. If, on the other hand, you want to self-publish, for a professional (or at least decent) job, you should contact others.

Adopt an artist!

Well, for one reason or another you have decided to dedicate yourself independently to the creation of the map but, aware of being a noob like myself in drawing, you thought it wise that someone else does it for you.

Ever since the world began, the web has been full of people who can’t wait to be covered in money and to work. Assholes are everywhere, even among artists or alleged artists, so be careful who you hire. I do not recommend contacting the notorious family friends with a passion for bricolage, instead contact freelancers whose portfolio you can see and who showcase all their previous works, it is an indication of professionalism and seriousness.

How to get it done?

For a D&D campaign

Here you can indulge yourself: it makes sense to commission a map of the game continent only if the sessions take place in person and not online, so it is reasonable to assume that the map is consulted by people sitting around a table. Therefore, the larger and cooler the map, the better. Mind you, the costs rise here, and you have two possibilities: the artist creates and prints the map himself and then sends it to you, or he sends you the source files and the printable version, which you will take to a copy shop to have it done. How wide, beautiful and refined you want it depends only on your pockets.

For a fantasy story

Maps for the fantasy stories have a purely role of consultation and boost of the epicness. Statistically speaking, your self-published fantasy novel will never become a best seller, so start with your feet on the ground and don’t screw up money for nothing: commission a digital map that you will insert in the first pages of your book, in black and white because otherwise the costs of press stand up too. If the artist knows what they are doing, they will ask you for the cage of the book and other editorial trifles, because the printing of any manuscript is subject to the so-called bleed, in essence if your book presents images you will have to behave differently during its digital layout versus a romance novel, for example.

Tricks for both

You still have to send the source files, so that you can modify them as you wish even through other professionals. If the platform you are using to commission the map is serious, there will be the possibility of including in the commission of the work a document that both you and the artist will have to sign, where it is certified that the latter grants you all the rights – commercial and copyright – on the work performed. Platforms like Fiverr automatically give you the rights, but don’t trust them: always have the artist sign an IP transfer agreement, i.e. the transfer of all rights on the work to the client (you).

If the purpose is to play an RPG with friends, the commercial rights will be useless. If you want to publish a book, they are essential.

By whom to get it done, and at what price?

I recommend that you look for an artist on the Upwork or Fiverr platforms. Knowledge of English is required, because the vast majority of the artists present there are foreigners. Just type in the search bar of these sites “fantasy map” to find dozens and dozens of professionals, whose price range varies from € 15 to more than € 400. Decide based on what you need and, in particular, on your pocket.

Bibliography

- General geography concepts for worldbuilding

- Traveling during the middle-ages

- Population and abitative density during the middle-ages

Thanks to Debby for all the maps, downloadable from here.

If you liked the article and can spare a couple seconds, leave a comment below!